Explore the Capabilities of Broadcasting in Julia Programming

Find out how to effortlessly utilize functions elementwise and explore more broadcasting strategies in Julia.

Julia is a relatively new, free, and open-source programming language. It has a syntax similar to that of other popular programming languages such as MATLAB and Python, but it boasts being able to achieve C-like speeds.

Unlike other languages that focus on technical computing, Julia does not require users to vectorize their code (i.e., to have one version of a function that operates on scalar values and another version that operates on arrays). Instead, Julia provides a built-in mechanism for vectorizing functions: broadcasting.

Broadcasting is useful in Julia for several reasons, including:

- It allows functions

that operate on scalar values

(e.g.,

cos(π)) to operate elementwise on an array of values, eliminating the need for specialized, vectorized versions of those functions. - It allows for more efficient memory allocation

in certain situations.

For example,

suppose we have a function,

func, and we want to computefunc(1, 2)andfunc(1, 3). Instead of broadcasting on[1, 1]and[2, 3], we can broadcast on1and[2, 3], avoiding the memory allocation for[1, 1].

On top of that, Julia provides a very convenient syntax for broadcasting, making it so anyone can easily use broadcasting in their code.

In this post, we will learn what broadcasting is, and we will see several examples of how to effectively use broadcasting.

This post assumes you already have Julia installed. If you haven't yet, check out our earlier post on how to install Julia.

What Is Broadcasting?

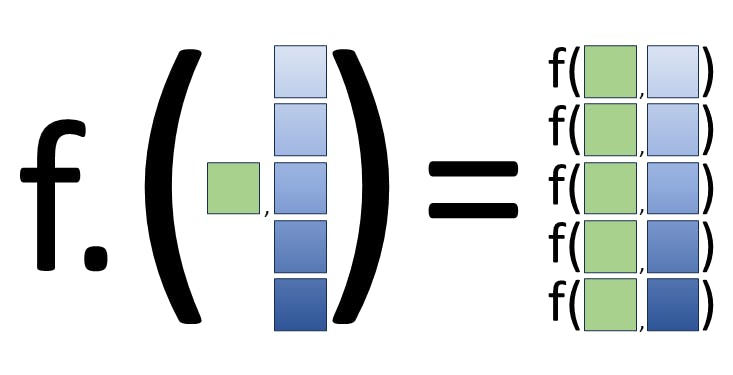

Broadcasting essentially is a method

for calling functions elementwise

while virtually copying inputs

so that all inputs have the same size.

(For example,

if two inputs to a broadcasted function f

are 1 and [1, 2, 3],

the first input is treated

as if it is [1, 1, 1]

but without actually allocating memory

for an array.

Then the function is applied

to each pair of inputs:

f(1, 1), f(1, 2), and f(1, 3).)

If that definition doesn't make sense right now, don't worry, the examples below will help illustrate.

The Dot Syntax

The first thing to know about broadcasting is that it is very convenient to use.

All you need to do is add dots.

For example,

if you want to take the square root

of a collection of values,

just add a dot (.):

julia> sqrt.([1, 4, 9]) # Notice the dot after `sqrt`

3-element Vector{Float64}:

1.0

2.0

3.0

Vectorizing Operators and Functions

As stated earlier,

Julia doesn't require

vectorized versions of functions.

In fact,

many functions don't even have methods

that take array inputs.

Take sqrt for example:

julia> sqrt([1, 4, 9]) # No dot after `sqrt`

ERROR: MethodError: no method matching sqrt(::Vector{Int64})

So, even though sqrt

doesn't have a vectorized version

explicitly defined,

the dot syntax still allows

sqrt to be applied elementwise.

The same applies to other functions and operators:

julia> [1, 2, 3] ^ 3 # No dot

ERROR: MethodError: no method matching ^(::Vector{Int64}, ::Int64)

julia> [1, 2, 3] .^ 3 # With dot

3-element Vector{Int64}:

1

8

27

julia> uppercase(["hello", "world"]) # No dot

ERROR: MethodError: no method matching uppercase(::Vector{String})

julia> uppercase.(["hello", "world"]) # With dot

2-element Vector{String}:

"HELLO"

"WORLD"

Vectorization even works with user-defined functions:

julia> myfunc(x) = x * 2

myfunc (generic function with 1 method)

julia> myfunc.([1, 2])

2-element Vector{Int64}:

2

4

Note that some functions

do have methods

that operate on arrays,

so be careful when deciding

whether a function should apply elementwise.

Take cos as an example:

julia> A = [0 π; π/2 π/6];

julia> cos(A) # Matrix cosine, *not* elementwise cosine

2x2 Matrix{Float64}:

-0.572989 -0.285823

-0.142912 -0.620626

julia> cos.(A) # Add a dot for computing the cosine elementwise

2x2 Matrix{Float64}:

1.0 -1.0

6.12323e-17 0.866025

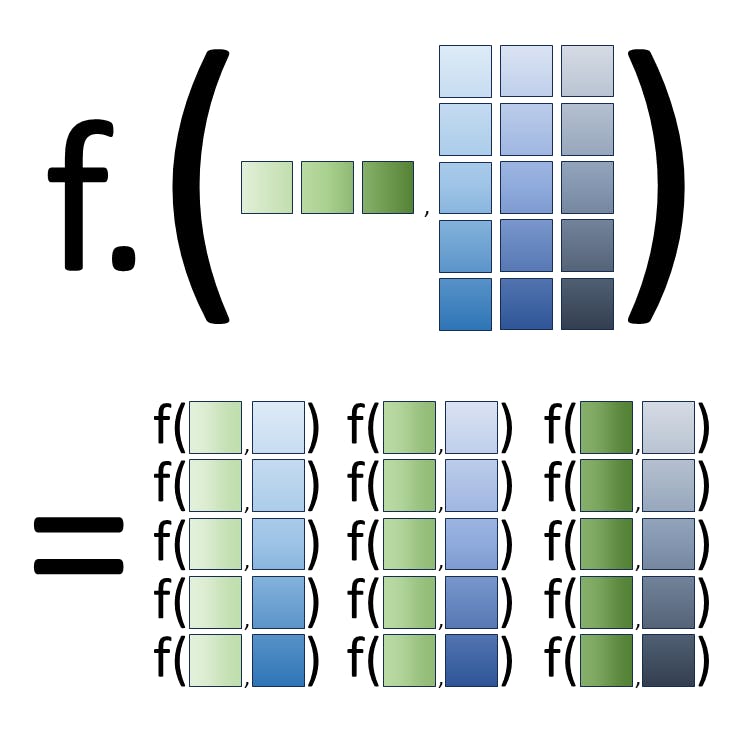

Broadcasting with Multiple Inputs

Broadcasting gets more interesting

when multiple inputs are involved.

Let's use addition (+) as an example.

We can add a scalar to each element of an array:

julia> [1, 2, 3] .+ 10

3-element Vector{Int64}:

11

12

13

julia> 10 .+ [1, 2, 3]

3-element Vector{Int64}:

11

12

13

We can also sum two arrays elementwise:

julia> [1, 2, 3] .+ [10, 20, 30]

3-element Vector{Int64}:

11

22

33

Broadcasting even works with arrays of different sizes. The only requirement is that non-singleton dimensions must match across inputs.

julia> [1 2 3; 4 5 6] .+ [10, 20] # Sizes: (2, 3) and (2,)

2x3 Matrix{Int64}:

11 12 13

24 25 26

julia> [1 2 3; 4 5 6] .+ [10 20] # Sizes: (2, 3) and (1, 2)

ERROR: DimensionMismatch: arrays could not be broadcast to a common size; got a dimension with lengths 3 and 2

julia> [1 2 3; 4 5 6] .+ [10 20 30] # Sizes: (2, 3) and (1, 3)

2x3 Matrix{Int64}:

11 22 33

14 25 36

In the first example

([1 2 3; 4 5 6] .+ [10, 20]),

the column vector [10, 20]

was added to each column

of the matrix,

while in the second working example

([1 2 3; 4 5 6] .+ [10 20 30]),

the row vector [10 20 30]

was added to each row

of the matrix.

Treating Inputs as Scalars

Sometimes, it is useful to broadcast over only a subset of the inputs. For example, suppose we have a function that scales an input matrix:

julia> myfunc2(X, a) = X * a

myfunc2 (generic function with 1 method)

Suppose we want to scale a given matrix by several different scale factors. The result should be an array of matrices, one matrix for each scale factor applied. We might try to use broadcasting:

julia> X = [1 2; 3 4]; a = [10, 20];

julia> myfunc2.(X, a)

2x2 Matrix{Int64}:

10 20

60 80

But the result is just one matrix!

We have one matrix because

we broadcasted over a and X,

not just a.

In this case,

we need to wrap X

in a single-element Tuple:

julia> myfunc2.((X,), a)

2-element Vector{Matrix{Int64}}:

[10 20; 30 40]

[20 40; 60 80]

Now we have the result we want:

an array where the first entry

is X scaled by a[1]

and the second entry

is X scaled by a[2].

So,

whenever you need to treat an input

as a scalar

for broadcasting purposes,

just wrap it in a Tuple.

Broadcasting with Dictionaries and Strings

Dictionaries and strings may act differently than expected in broadcasting, so let's clarify some things here.

First, attempting to broadcast over a dictionary will throw an error:

julia> d = Dict("key1" => "hello", "key2" => "world")

Dict{String, String} with 2 entries:

"key2" => "world"

"key1" => "hello"

julia> println.(d)

ERROR: ArgumentError: broadcasting over dictionaries and `NamedTuple`s is reserved

There are different solutions depending on the context. For example:

- Treat the dictionary as a scalar:

julia> println.((d,)); # Note that `d` is wrapped in a `Tuple` Dict("key2" => "world", "key1" => "hello") - Broadcast over the values explicitly:

julia> println.(values(d)); world hello

Regarding strings, strings are treated as scalars, not as collections of characters. For example:

julia> string.("string", [1, 2])

2-element Vector{String}:

"string1"

"string2"

(The above would have errored

if strings were not treated as scalars,

because length("string") is 6,

whereas length([1, 2]) is 2.)

To broadcast over the characters

in a string,

use collect:

julia> string.(collect("string"), 1:6)

6-element Vector{String}:

"s1"

"t2"

"r3"

"i4"

"n5"

"g6"

Summary

In this post, we learned what broadcasting is, and we saw several examples of how to effectively use broadcasting to apply functions elementwise.

Have any further questions about broadcasting? Feel free to ask them in the comments below!

Does broadcasting make sense now? Move on to the next post to learn about Julia's type system! Or, feel free to take a look at our other Julia tutorial posts!

Additional Links

- Julia documentation about broadcasting:

- Installing Julia and VS Code - A Comprehensive Guide

- How-to guide for installing Julia and VS Code.

- Understanding the Julia Type System

- Introduction to how Julia handles types.